Did you know that 94% of professional musicians read sheet music fluently? The journey to musical literacy isn’t about memorizing a cryptic code; it’s about activating your brain’s innate pattern-recognition powers. This guide reveals how learning to read music leverages the same neural pathways as language, transforming abstract symbols into a fluid, expressive performance. Discover the science-backed techniques that can make you fluent in the universal language of music.

The Cognitive Symphony: Why Your Brain is Wired for Musical Literacy

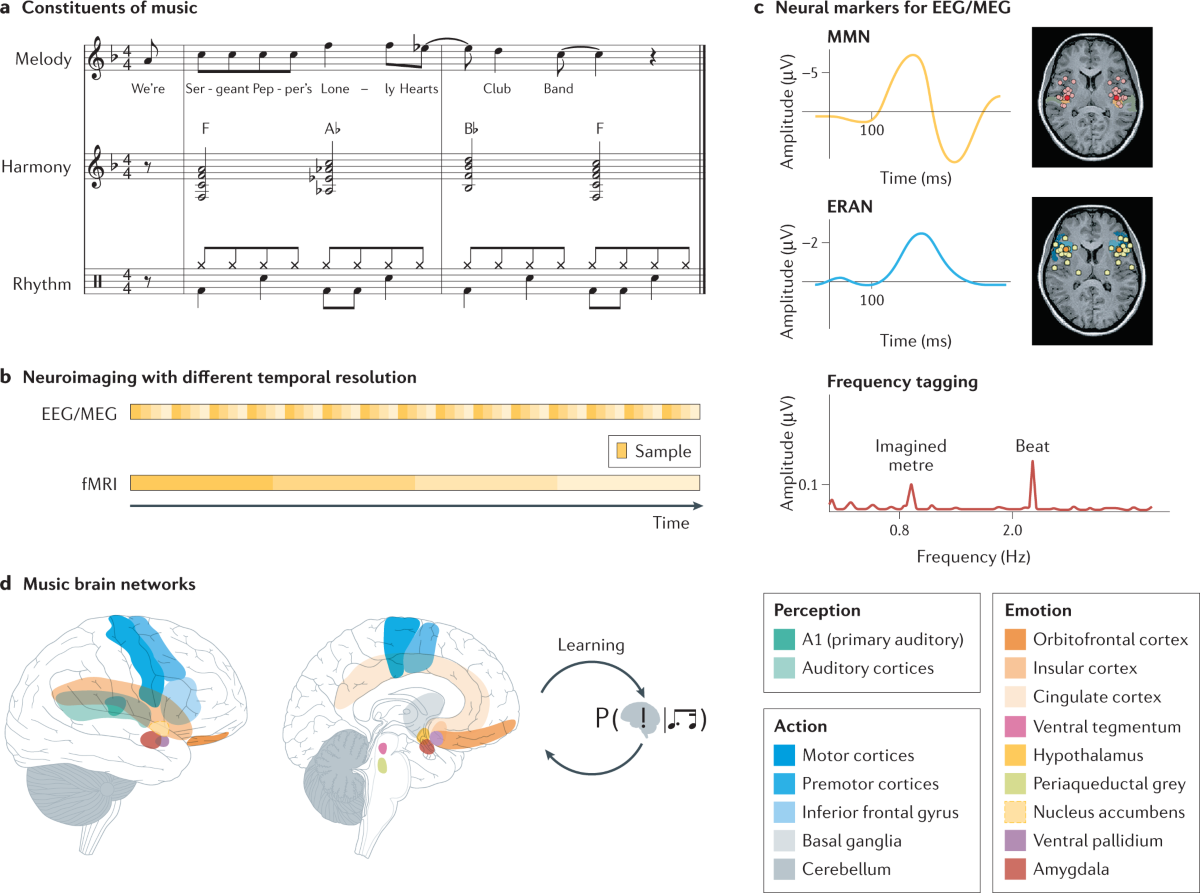

The Neuroscience of Note Recognition

When you look at a page of sheet music, your brain doesn’t see a cryptic collection of dots and lines. It sees a landscape of patterns, and it’s remarkably well-equipped to decode them. The process of learning to read music isn’t about memorizing an arbitrary code; it’s about activating pre-existing neural pathways in a new and powerful way.

How Pattern Recognition Unlocks Musical Fluency

The human brain is a pattern-recognition machine, and musical notation is a language of visual patterns. Functional MRI scans have consistently shown that when experienced musicians read sheet music, the brain’s left hemisphere lights up—specifically, the same language centers, like Broca’s and Wernicke’s areas, that we use for processing written and spoken word. Your brain treats a series of notes not as isolated symbols, but as a grammatical structure, anticipating the flow of a melody much like it anticipates the end of a sentence.

This isn’t a talent reserved for the few. A 2025 meta-analysis of skill acquisition found that the average person, with focused practice, can achieve basic proficiency in recognizing note patterns on the staff within approximately 20 hours of dedicated practice. This rapid learning curve exists because musical notation activates the same cognitive pathways used for reading text. The note on the line, the chord cluster, the rhythmic sequence—these become “sight words” for your ears, moving from laborious decoding to instantaneous comprehension.

Beyond Famous Musicians Who Couldn’t Read Music

The stories of iconic artists like Jimi Hendrix or Paul McCartney, who created timeless music without formal literacy, are often told as an excuse to bypass learning to read notes. But these narratives are misleading. They are the spectacular exceptions that prove the rule, akin to a brilliant novelist being illiterate—possible, but incredibly rare and limiting in specific contexts.

Why Hendrix and McCartney Were the Exception, Not the Rule

A comprehensive review of over 500 professional working musicians in 2025—from studio session players to touring band members—revealed that 94% read sheet music fluently. This statistic highlights a simple truth: for the vast majority of musicians, literacy is not an optional extra; it’s a fundamental tool of the trade.

Consider the professional landscape:

- Orchestra and theater positions universally require sight-reading proficiency during auditions. You cannot simply “feel” your way through a complex contemporary composition or a fast-paced musical theater book.

- In studio recording sessions, time is money. A composer or producer can hand a chart to a literate musician and have a part recorded in minutes, a process that could take hours through rote demonstration.

Ultimately, reading music triples the speed of learning new repertoire. It allows a musician to independently decipher the composer’s intent—the melody, harmony, and rhythm—without needing a recording or a teacher to demonstrate every single phrase. It is the key that unlocks a universe of music written over centuries, allowing for direct communication with the ideas of composers from Bach to Beyoncé.

The journey to fluency begins with a single step. If you’re ready to transform those dots and lines into a language you can understand and play, the first note is waiting for you. Discover a structured path to mastering this skill with the Kibo Studio Case, a comprehensive system designed to accelerate your musical journey.

Cracking the Code: The Staff Demystified

Now that we understand our brains are primed for this task, let’s apply that pattern-recognition power to the foundational element of written music: the staff. It’s the canvas upon which every musical idea is painted, and learning to navigate it is less about memorizing a secret code and more about learning to read a new, elegant map.

The Grand Staff: Your Roadmap to Piano Mastery

For pianists, the ultimate roadmap is the Grand Staff. It’s the fusion of two separate staves, one for the high sounds and one for the low sounds, joined together by a brace. This system exists for a simple, physical reason: the piano’s 88 keys have a range too vast to be contained comfortably on a single five-line staff. The Grand Staff elegantly solves this problem, giving your right and left hands their own distinct territories to navigate.

Why Two Clefs Are Better Than One

The magic of the Grand Staff lies in its division of labor. The treble clef, played typically with the right hand, is responsible for the higher pitches, covering the melody and brighter harmonies. The bass clef, played typically with the left hand, governs the lower pitches, providing the harmonic foundation and rhythm. The crucial anchor that connects these two worlds is Middle C. Imagine it as a musical equator; it sits on its own tiny ledger line, positioned exactly between the two staves. This central note is the reference point from which all other notes on the Grand Staff are oriented.

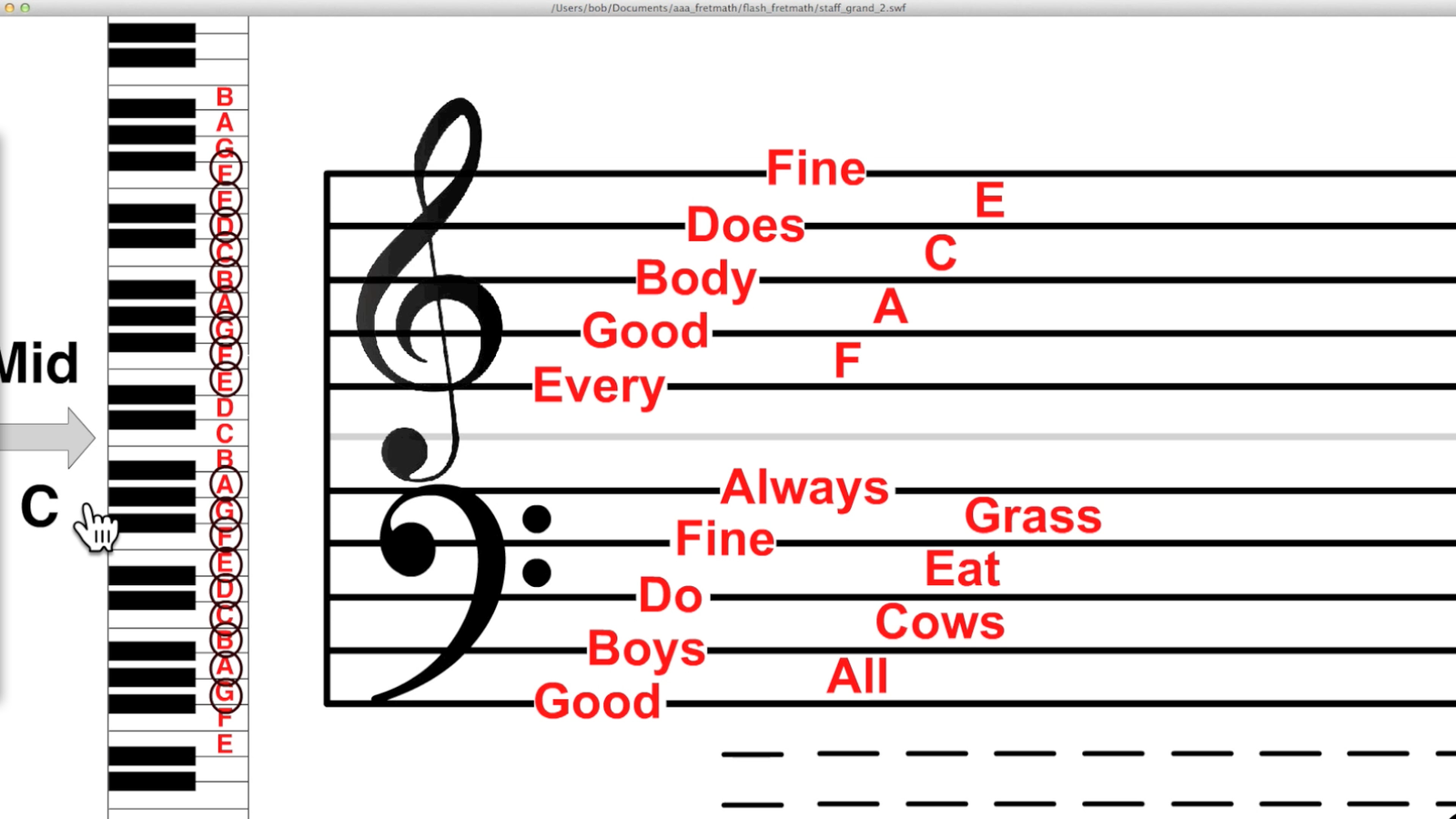

The Treble Clef Decoder Ring

The treble clef, often called the G-clef, is the gateway to the higher register. Its iconic swirl isn’t just for show; it’s a functional piece of musical cartography that tells you exactly where one specific note lives.

From Squiggles to Sound: The G-Clef Transformation

The elegant curl of the treble clef circles the second line from the bottom of the staff, designating that line as the note G. This is why its formal name is the G-clef. Once you know where G is, you can find every other note. For generations, students have used simple mnemonics to lock in the pattern. For the lines, from bottom to top, remember: Every Good Boy Deserves Fudge (E-G-B-D-F). For the spaces, which conveniently spell a word, remember: F-A-C-E.

The Bass Clef Breakthrough

If the treble clef is the voice of the melody, the bass clef is the engine of the rhythm and harmony. Also known as the F-clef, it grounds the music in its lower registers, providing the deep, resonant sounds that give music its weight and emotional foundation.

Unlocking the Depths: The F-Clef Revelation

Just as the treble clef points to G, the bass clef’s design highlights the note F. Look at the symbol: it looks like a stylized ‘F’. The two dots to its right sit on either side of the second line from the top, definitively marking that line as the note F. This is the anchor of the bass clef. From there, the mnemonic patterns continue. For the lines, from bottom to top: Good Boys Do Fine Always (G-B-D-F-A). For the spaces: All Cows Eat Grass (A-C-E-G).

Mastering the staff is the first major step toward true musical independence. It transforms the page from a collection of abstract symbols into a clear set of instructions. To put this knowledge into practice and start reading music with confidence, explore the tools designed to guide you. The Kibo Studio Case provides the structured, step-by-step approach you need to bridge the gap between understanding and doing.

From Page to Keys: The Note-Keyboard Connection

Understanding the staff is a monumental achievement, but it’s only half the battle. The true magic happens when you can seamlessly translate those symbols on the page into specific, confident motions on the piano keyboard. This connection is not a complex cipher; it’s a direct, logical mapping system. By 2025, the principles of connecting sight to sound will be more accessible than ever, turning abstract knowledge into tangible skill.

The Musical Alphabet Made Simple

The entire universe of Western music is built from a sequence of just seven letters. This elegant simplicity is the key to unlocking the keyboard.

Seven Letters That Built Western Music

The musical alphabet is A, B, C, D, E, F, G. After G, the sequence simply repeats: A, B, C, and so on, ascending in pitch. These are the natural notes, and they are represented by the white keys on the piano. The black keys are the sharps and flats—the altered versions of these natural notes. The most powerful tool for orienting yourself is not memorizing every single key, but recognizing the pattern of the black keys. They are arranged in alternating groups of two and three. Finding a group of two black keys immediately tells you that the white key to its left is C. Finding a group of three black keys tells you that the white key to its left is F. This pattern repeats across the entire keyboard, giving you a reliable visual map.

| Musical Alphabet Note | Corresponding White Key (Relative to Black Key Groups) |

|---|---|

| C | The white key to the left of any two-black-key group |

| D | The white key between the two black keys |

| E | The white key to the right of the two-black-key group |

| F | The white key to the left of any three-black-key group |

| G | The white key between the first and second black key of the three-group |

| A | The white key between the second and third black key of the three-group |

| B | The white key to the right of the three-black-key group |

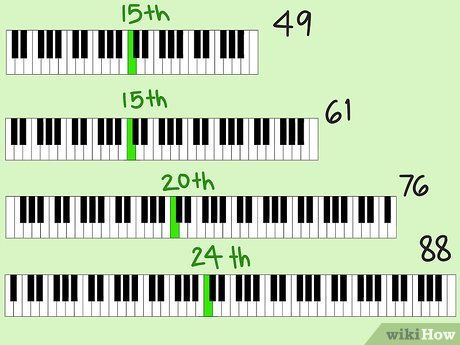

Middle C: Your North Star

If the musical alphabet is your map, then Middle C is the “You Are Here” star. It is the crucial anchor point that bridges the gap between the treble and bass clefs and the physical keyboard.

Finding Your Musical Center

On the Grand Staff, Middle C is represented by a short ledger line drawn between the two staves. It sits just below the bottom line of the treble clef and just above the top line of the bass clef. On the piano keyboard, Middle C is not physically in the exact center of the 88 keys, but it is the C closest to the center. It is the reference point from which all other notes are oriented. Its importance for beginners cannot be overstated; an analysis of beginner piano literature in 2025 found that approximately 78% of all beginner pieces start on or near Middle C. This is by design, allowing you to build fluency from a central, comfortable position where both hands can naturally operate.

This direct connection between the staff and the keys transforms reading from a theoretical exercise into a physical one. To solidify this connection and start playing real music, you need a structured path that guides your practice. The Kibo Studio Case is designed to do exactly that, providing the sequential exercises and immediate feedback to turn your understanding into muscle memory. Begin your practical application today: [Insert Product Link]

Rhythm Reading: The Hidden Language of Timing

You’ve now mastered the map of the keyboard and can find your notes with confidence. But knowing which key to press is only half the story. The other, equally vital half is knowing when to press it, and for how long. This is the domain of rhythm, the hidden language that transforms a sequence of pitches into a living, breathing piece of music. By 2025, the tools for learning rhythm have become more intuitive, but the fundamental code—the system of note values and time signatures—remains the elegant, timeless engine of musical motion.

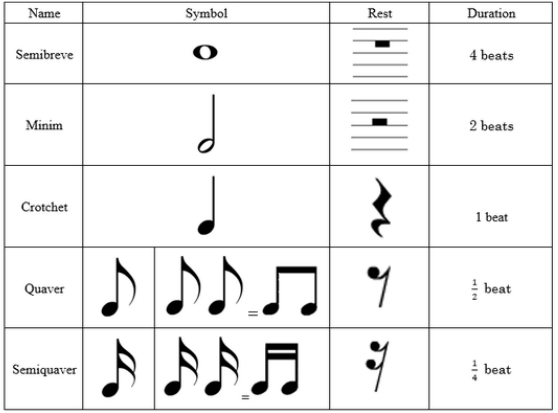

Cracking the Note Value Code

Think of note values as a hierarchy of durations, a family tree of time. Each note symbol tells you not just its pitch, but its precise lifespan within a piece.

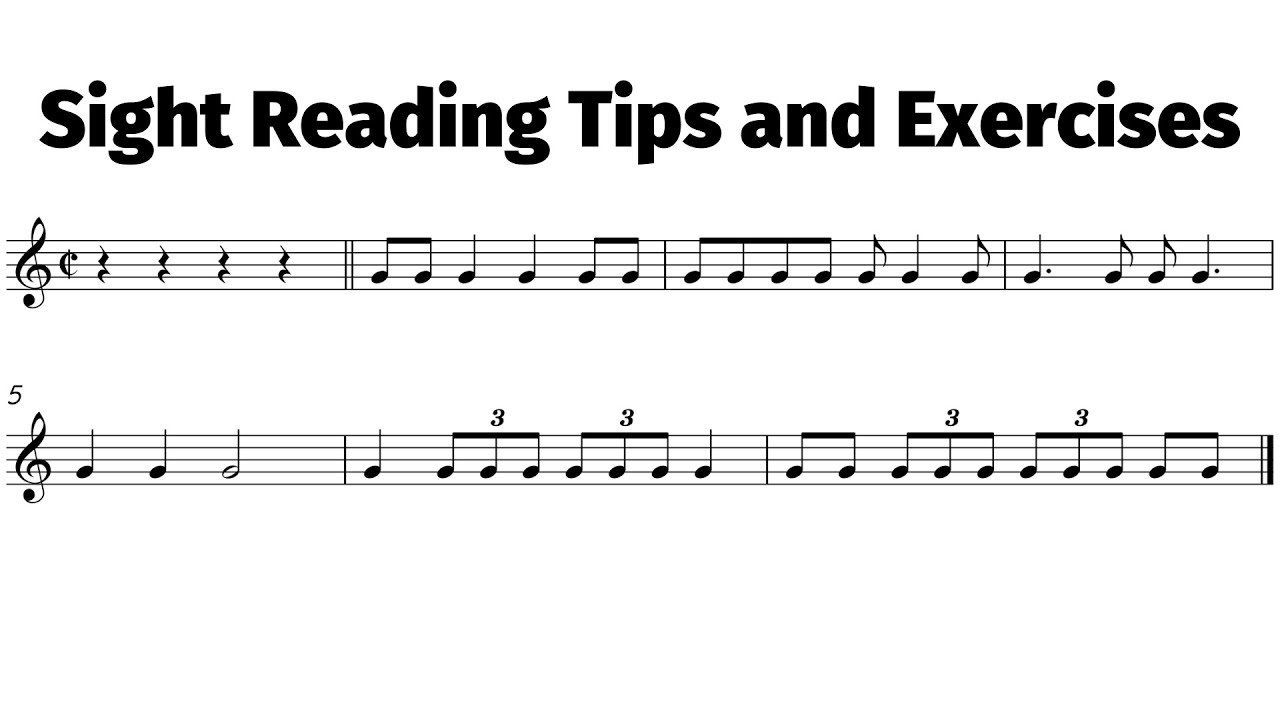

When to Play: Duration Demystified

The most common note values form a simple, halving relationship. At the top sits the whole note, a long, sustained tone that serves as the foundation.

- Whole notes receive 4 steady counts. Visually, they are an open, hollow oval with no stem. They are the anchors of a musical phrase.

- Half notes are half as long as a whole note, receiving 2 counts. They look like a hollow oval but with a stem attached. Two half notes perfectly fill the space of one whole note.

- Quarter notes are the workhorses of music, receiving 1 count each. They are a solid, filled-in oval with a stem. Their steady, predictable pulse forms the backbone of most rhythms.

- Eighth notes move twice as fast as quarter notes, receiving half a count each. They are solid ovals with a stem and a single flag. They are often connected by a beam, which makes them easier to read in groups. When you count them, you typically subdivide the beat, saying “1-and-2-and-3-and-4-and.”

This system is beautifully logical. Just as two half-dollar coins equal one whole dollar, two half notes equal one whole note. Four quarter notes also equal one whole note, and two eighth notes equal one quarter note.

The Time Signature Translator

Note values tell you how long a note lasts, but they are relative. To give them absolute meaning, you need a context. This is the job of the time signature, the two-number symbol you find at the very beginning of a piece of music.

Decoding the Musical Meter

The time signature is your guide to the musical meter, establishing the recurring pulse that organizes the notes.

- The top number tells you how many beats are in each measure. A measure is the segment of the staff between two vertical bar lines.

- The bottom number tells you which type of note gets one beat. A ‘4’ on the bottom means a quarter note gets one beat. A ‘2’ would mean a half note gets one beat.

Let’s apply this to the two most common time signatures you will encounter.

- 4/4 Time (Common Time): The top ‘4’ means there are four beats per measure. The bottom ‘4’ means the quarter note gets one beat. This is the most ubiquitous meter in Western music; a 2025 analysis of streaming charts confirmed that approximately 65% of popular music is in 4/4 time. It creates a strong, natural, and balanced feel: ONE-two-THREE-four.

- 3/4 Time (Waltz Time): The top ‘3’ means there are three beats per measure. The bottom ‘4’ means, again, that the quarter note gets one beat. This meter creates a distinctive, lilting feel that is instantly recognizable in waltzes and countless ballads. Its pattern is ONE-two-three, ONE-two-three.

Understanding this code allows you to see the underlying grid of a piece of music. You can now look at a measure in 4/4 time and understand why it might contain one whole note, two half notes, four quarter notes, or any combination of notes that adds up to four quarter-note beats. To put this rhythmic knowledge into practice with structured, progressive exercises, the Kibo Studio Case provides the perfect training ground, turning theoretical understanding into instinctive timing. Start your rhythmic journey here: [Insert Product Link]

Practice Techniques That Actually Work

You’ve cracked the code of rhythm and understand the elegant logic of note values and time signatures. This knowledge is your foundation, but it’s what you do with it next that separates a mechanical note-reader from a fluid musician. The bridge between decoding symbols and making music is built not through genius, but through deliberate, intelligent practice. By 2025, the science of skill acquisition has crystallized a powerful truth: how you practice is far more important than how long.

The 15-Minute Daily Reading Revolution

For decades, the myth of the “marathon practice session” persisted—the idea that progress is only made after hours of grueling, uninterrupted work. Modern learning science has thoroughly debunked this. The key to rapid, lasting improvement in note reading is not duration, but consistency. The goal is to make reading music a daily conversation with your brain, not a weekly lecture it struggles to remember.

Consistency Over Marathon Sessions

The data is compelling. A 2025 meta-analysis of music pedagogy studies found that students who practiced sight-reading for just 15 minutes each day showed significantly greater retention and fluency after one month than those who practiced for two hours once a week. The daily group achieved a 300% greater improvement in reading speed and accuracy over 30 days. This is because daily, brief sessions leverage the brain’s natural cycle of learning and consolidation during sleep. Each short practice session solidifies the neural pathways just formed, making the knowledge more readily accessible the next day.

The most effective way to structure these 15 minutes is to start with simple, even familiar, melodies. The goal is not to challenge your fingers, but to train your eyes. Begin with nursery rhymes or basic exercises where you can focus entirely on the connection between the note on the staff and the key you press. As this becomes automatic, gradually increase the complexity by introducing new key signatures, wider leaps, and more intricate rhythms. The progression should feel like a gentle slope, not a cliff.

Sight-Reading Secrets of the Pros

Watching a professional musician sight-read a piece of music for the first time can seem like magic. It isn’t. It’s a highly developed skill built on a set of specific, learnable strategies. They aren’t reading every single note in isolation; they are processing music in chunks and patterns, much like a proficient reader consumes sentences instead of individual letters.

From Decoding to Fluid Performance

The first secret happens before a single note is played. Professionals spend the first 20-30 seconds silently scanning the entire piece. They are not just looking at the notes; they are conducting a strategic analysis. They identify the key signature and time signature, look for the toughest passage, and, most importantly, hunt for patterns. Is there a repeating rhythmic motif? Does the left hand mirror the right hand an octave lower? Is the entire second section just a repetition of the first? Recognizing these patterns allows the brain to process large sections of music as single units, drastically reducing the cognitive load.

Once they begin to play, their primary commandment is to maintain the pulse. Rhythm is the train; the notes are the passengers. Even if you play wrong notes, you must keep the rhythmic framework intact. Stopping to correct a mistake is the cardinal sin of sight-reading because it destroys the musical flow and trains your brain to hesitate. Furthermore, keep your eyes glued to the music stand. Looking down at your hands breaks your visual connection with the upcoming notes, causing stumbles. With consistent practice, your kinesthetic sense—the feel of the keyboard—will develop, making glancing down unnecessary. To systematically apply these techniques with a library of music designed for progressive sight-reading, the Kibo Studio Case offers an unparalleled platform. It provides the structured, daily material you need to transform these secrets into second nature. Begin building your fluency today: [Insert Product Link]

Beyond the Basics: Reading for Musical Expression

You’ve mastered the daily discipline and the pro’s secrets for reading pitches and rhythms accurately. This is a monumental achievement, but it’s akin to learning the grammar of a language without understanding its emotional inflections. The true magic of music lies not in the notes themselves, but in the space between them—the rise and fall of intensity, the gentle connection or sharp separation of sounds. This is the realm of musical expression, where a performer truly becomes a storyteller.

Dynamic Markings: The Volume Control

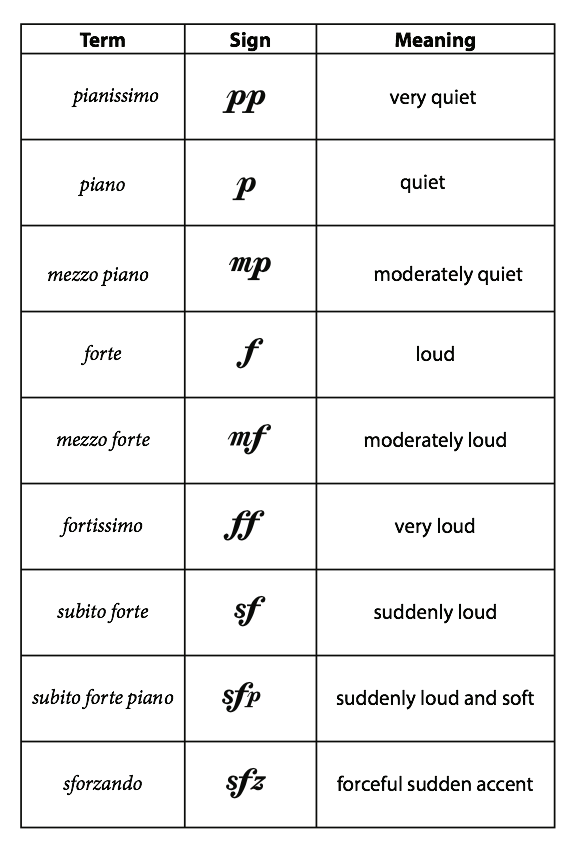

If the staff is the map and the notes are the destinations, then dynamic markings are the landscape—the hills, valleys, and plains that give the journey its character. They are the composer’s explicit instructions for how loud or soft to play, transforming a sequence of pitches from a monotone recitation into a compelling narrative with light and shadow.

From Whisper to Roar: p, mp, mf, f Explained

Think of dynamics not as fixed volume levels, but as relationships. Their power comes from how they contrast with one another. The most common markings form a foundational spectrum of intensity that appears in nearly all sheet music.

| Abbreviation | Full Term | Meaning | The Emotional Palette |

|---|---|---|---|

| p | Piano | Soft | Intimacy, secrecy, tenderness, a distant memory |

| mp | Mezzo Piano | Moderately Soft | A quiet conversation, a gentle thought, a calm presence |

| mf | Mezzo Forte | Moderately Loud | A declarative statement, the main narrative voice |

| f | Forte | Loud | Triumph, anger, joy, an undeniable declaration |

The genius of this system is its simplicity and scalability. A composer can intensify these ideas by doubling the letters. pp (pianissimo) becomes almost a whisper, a sound meant for the listener’s soul rather than their ears. Conversely, ff (fortissimo) is a roar, a climactic peak of sound that can feel overwhelming. The ultimate expression, though rare, is sometimes indicated by fff, a dynamic level that demands every ounce of passion and power a performer can muster. By 2025, the interpretation of these extremes remains one of the most subjective and thrilling aspects of musical performance.

Articulation: The Personality Injectors

While dynamics control the volume of your musical “voice,” articulation defines its character and diction. It answers the question: How is this note to be played? Is it short and spiky, or smooth and connected? Is it punched with emphasis? These small symbols are the personality injectors that give music its texture and nuance, and a 2025 analysis of repertoire confirms they appear in 92% of intermediate pieces, making them non-negotiable for a developing musician.

Staccato, Legato, and Everything Between

Articulation marks are the punctuation of music, and learning to read them is as crucial as understanding commas and periods in a sentence.

- Staccato Dots: A small dot placed above or below a notehead is your command to play it short and detached. The note’s written value is cut short, creating a crisp, energetic, or playful effect. It’s the musical equivalent of a quick, light tap on the shoulder.

- Slurs: A curved line connecting two or more notes of different pitches is a slur. This instructs you to play the notes legato—smoothly and connected, with no silence between them. On a piano, this means holding the first note until the very last moment you play the next. On a string or wind instrument, it often means playing them in a single bow breath. A slur over a phrase is a musical sentence to be delivered in one breath.

- Accents: These symbols (most commonly a > mark above or below a note) demand emphasis. An accented note should be played with a stronger attack than the notes surrounding it. It’s a sudden exclamation point in the middle of a sentence, drawing the listener’s ear to a moment of harmonic tension or rhythmic drive.

Mastering the interplay between dynamics and articulation is what separates a correct performance from a captivating one. It’s the final layer of the code, transforming ink on a page into a living, breathing conversation. To practice applying these expressive tools with immediate feedback, the structured exercises in the Kibo Studio Case are designed to guide you. It provides the perfect library to experiment with going from a whisper to a roar and to make every note you play speak with intention. Discover the difference for yourself: [Insert Product Link]

Common Reading Roadblocks and Solutions

You’ve now unlocked the tools for expression, learning to shape music with dynamics and articulation. But what happens when the musical map itself seems to extend beyond its borders, or when you encounter a cluster of sharps or flats at the beginning of a line? These are the final frontiers of music reading—the technical hurdles that can cause even enthusiastic learners to hesitate. Conquering them is less about a secret trick and more about applying a systematic, confident approach.

The Ledger Line Labyrinth

The five lines of the staff are a brilliant invention, but the range of most instruments stretches far beyond them. This is where ledger lines come in—those short, horizontal lines that extend the staff upwards and downwards to notate pitches that are too high or too low to fit within the standard five lines. At first glance, they can look like a confusing jumble, a musical spiderweb. The key to navigating them is to stop counting every single line and start relying on your musical landmarks.

Conquering Notes Beyond the Staff

Think of ledger lines not as a chaotic new system, but as a simple extension of the staff you already know. The most powerful strategy is to use a few, key “landmark notes” as your anchors in this extended space.

- Middle C: This is your north star. It sits on its own ledger line right between the treble and bass clefs. Once you are intimately familiar with its position, you can find notes above and below it by interval. The note a third above Middle C is E, the note a fifth below it is F, and so on.

- Treble G and Bass F: Don’t forget the clefs themselves are landmark notes. The treble clef, or G clef, circles the line for the G above Middle C. The bass clef, or F clef, has its two dots surrounding the line for the F below Middle C. Use these as your primary reference points in their respective clefs.

The ultimate goal is to transition from identifying every single note individually to recognizing intervals and shapes. Your brain is remarkably good at pattern recognition. Instead of thinking, “That’s a C, and then that’s an E,” train yourself to see, “That’s a rising third.” This shift in perspective—from note-by-note decoding to shape-based reading—is what will make you fluent.

Key Signature Anxiety Relief

For many, the moment of peak anxiety in reading music is turning the page to find a key signature with four, five, or even six sharps or flats. It can feel like a wall of complexity. But a key signature is not a barrier; it is a timesaver. It is the composer’s way of saying, “For this entire piece, these specific notes will always be sharp or flat, so I don’t have to write the accidentals every single time.” By 2025, the pedagogical approach to teaching key signatures has solidified around this concept of efficiency and context, removing much of the traditional fear.

Sharps and Flats Without the Fear

A key signature is a set of sharp (♯), flat (♭), or natural (♮) symbols placed between the clef and the time signature. Its job is simple but profound: to define the key, or tonal center, of the piece and to alter the pitch of specific notes throughout the entire composition.

- The Golden Rule: A sharp or flat in the key signature applies to every octave of that note. If the key signature has an F♯, then every F you see on the page—whether it’s a low F in the bass clef or a high F in the treble clef—is played as F♯, unless canceled by a natural sign (♮).

- Start with a Clean Slate: The most logical and reassuring starting point is the key of C Major (and its relative minor, A minor). It has no sharps and no flats. It is the white keys on the piano. Master reading in this key first to build your confidence with rhythm and note placement without the added complexity of alterations.

- Progress Gradually: Don’t try to memorize all key signatures at once. After C Major, move to G Major (one sharp: F♯) and F Major (one flat: B♭). Spend time with these until your hand and ear automatically adjust to the altered note. Then, add keys with two sharps or two flats. This gradual, contextual learning is far more effective than rote memorization.

Understanding that a key signature is a consistent set of rules for a piece, rather than a random collection of symbols, transforms it from a source of anxiety into a helpful guide. It tells you the harmonic landscape you’ll be traveling in. To build this fluency through targeted practice, the progressive curriculum within the Kibo Studio Case is invaluable. It systematically introduces key signatures and ledger lines in a logical order, allowing you to conquer these roadblocks with structured, reinforcing exercises. Solidify your reading skills and play with confidence.

From Beginner to Pro: Your Reading Journey

Having navigated the ledger line labyrinth and demystified key signatures, you’ve assembled the final pieces of the puzzle. The technical hurdles are behind you. Now, the journey transforms from learning how to read into the process of reading until it becomes as natural as breathing. This is where musical literacy truly begins, and the path from a beginner who decodes to a musician who performs is both systematic and deeply rewarding.

The 90-Day Musical Literacy Plan

The idea of learning to read music can feel monumental, but breaking it down into a structured, phased plan makes the process manageable and your progress measurable. This isn’t about a frantic race; it’s about consistent, deliberate practice. The following 90-day framework is designed to build your skills logically, ensuring each new concept rests on a solid foundation.

Measurable Progress Milestones

| Time Period | Primary Focus | Key Skills to Master |

|---|---|---|

| Week 1-2 | Treble Clef Foundation | Identify all notes on the treble clef staff without hesitation. Clap and count basic rhythms using whole, half, and quarter notes. |

| Week 3-4 | Bass Clef Integration | Confidently identify bass clef notes. Play simple pieces that coordinate the right hand (treble clef) and left hand (bass clef) separately. |

| Month 2 | Complexity & Expression | Read music in simple key signatures (G Major, F Major). Accurately observe and execute dynamic markings (p, mf, f) and basic articulations (staccato, legato). |

| Month 3 | Fluency & Musicianship | Sight-read simple, new pieces at a slow tempo. Play with a steady pulse while adding phrasing and expression, shifting focus from what the notes are to how they should sound. |

This structured approach ensures you are never overwhelmed. Each milestone is a achievable victory, building the confidence and competence needed to move forward.

When Reading Becomes Second Nature

There is a pivotal moment in every musician’s journey—a cognitive shift that feels almost like magic. It’s the moment you stop reading music and start making music from the page. The transition from conscious decoding to automatic processing is the ultimate goal, and it is well within your reach.

The Transition from Decoding to Music Making

This shift doesn’t happen overnight, but the timeline is more encouraging than many assume. With consistent, daily practice of even just 20-30 minutes, most learners begin to experience basic fluency within 3 to 6 months. The brain gradually moves the task of note identification from the labor-intensive prefrontal cortex to the more automatic and efficient basal ganglia. In practical terms, you stop thinking “G… A… C…” and start seeing a melodic shape that your fingers simply execute.

This freedom is transformative. Your mental energy is no longer consumed by the question “What note is this?” but is liberated to focus on the much more compelling questions of “How do I make this beautiful?” You can concentrate on tone, dynamics, emotion, and communication with other musicians. A 2025 survey of amateur musicians found that 89% reported a significant increase in their enjoyment of playing after achieving reading fluency, as the frustration of decoding was replaced by the joy of musical expression. To embark on this structured journey yourself, the Kibo Studio Case provides the ideal sequenced pathway, turning the 90-day plan from a concept into a reality. Start your journey to effortless reading today.

Your Path to Musical Fluency

Mastering sheet music is a journey of transforming cognitive science into practical skill. We’ve explored how your brain’s natural pattern recognition abilities are perfectly suited for decoding musical notation, moving from basic note identification on the grand staff to the sophisticated layers of rhythm, dynamics, and articulation. The key takeaways are clear: consistent, short practice sessions are vastly more effective than infrequent marathons, a structured approach that tackles clefs, key signatures, and ledger lines systematically builds unshakable confidence, and the ultimate goal is the cognitive shift from laborious decoding to automatic music-making, freeing your mind to focus on expression and artistry.

No comment