Did you know that consistent 20-minute daily practice can establish basic music reading proficiency in just 3-6 months? The journey to piano sheet music literacy isn’t about memorizing an abstract code but training your brain in sophisticated pattern recognition. This comprehensive guide dismantles the psychological barriers that hold adult beginners back, revealing how modern cognitive science combines with traditional techniques to accelerate your path to musical fluency. The most effective approach to learning does not lie in choosing between different techniques, but in understanding how sight-singing, ear training, chord charts and playing by ear work together to build a comprehensive system of musical skills.

The Unspoken Truth About Music Literacy

The Great Divide in Piano Education

The Traditionalist’s Argument

For centuries, the ability to read sheet music was not just a skill but the very definition of musical literacy. The classical training model, perfected over generations, insists that sheet music is the non-negotiable bedrock of a serious musical education. It provides the structural foundation for understanding complex compositions, from a Bach fugue to a Ravel concerto, allowing a pianist to see the architecture of the music—the interplay of melody, harmony, and rhythm—laid out before them. This isn’t merely about tradition; it’s about a standardized communication method. A pianist in Tokyo can sit down with a musician from Berlin and, through the universal language of sheet music, create a coherent performance without sharing a common spoken word. It is the original and most precise open standard for musical collaboration.

The Modern Approach Revolution

The digital age has fundamentally challenged this centuries-old paradigm. A revolution is underway, fueled by learning platforms and apps that prioritize playing by ear, using synthesia-style falling notes, or following chord charts. This approach points to the undeniable success stories of famous musicians, from the Beatles to Erroll Garner, who created timeless music without ever becoming fluent readers. The modern method also addresses a critical, often unspoken, hurdle: the psychological barrier for adult beginners. The prospect of learning what looks like a complex, foreign language can be profoundly discouraging. For many, the immediate joy of playing a familiar melody by ear or through visual mimicry is a more compelling and sustainable entry point than the slow, methodical study of musical notation.

What Research Actually Shows About Learning Speed

Cognitive Science of Music Reading

The process of learning to read music is less about memorizing an abstract code and more about training the brain in a specific type of pattern recognition. Cognitive studies suggest that with consistent, focused practice, the foundation for basic proficiency can be established in a timeline of 3 to 6 months. This is the period where the brain begins to automatically associate the position of a note on the staff with a specific key on the piano and a corresponding finger movement, creating a powerful triad of visual, aural, and kinesthetic understanding. This integration of muscle memory with visual processing is the key. The brain starts to chunk information—seeing a common chord shape, for instance, as a single unit rather than three individual notes. The most critical factor for most learners isn’t the duration of a single practice session, but its consistency. Research indicates that crossing a threshold of about 20 minutes of daily practice is often enough to create the neural pathways required for sustainable progress, making the skill far more accessible than many assume.

Comparative Learning Methodologies

When we compare the efficacy of different learning methodologies, the picture is more nuanced than a simple “best” method. The choice between traditional sheet music, chord charts, and playing by ear often depends on the learner’s goals and innate strengths.

| Methodology | Primary Focus | Time to Initial Proficiency (Playing a Simple Melody) | Long-Term Retention & Transferability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Sheet Music | Decoding symbolic notation | Slower (1-3 months) | High. Skills transfer to any other instrument and allow for learning complex, unfamiliar music independently. |

| Chord Charts | Harmonic structure and rhythm | Faster (2-4 weeks) | Medium. Excellent for accompaniment and popular music, but limited for melodic or complex classical pieces. |

| Play-by-Ear / Mimicry | Aural recognition and muscle memory | Fastest (1-2 weeks for a simple tune) | Variable. Highly dependent on aural skills; difficult to apply to music the learner cannot already hear. |

What the data reveals is that while methods like mimicry offer a faster initial reward, the deep, structural understanding fostered by sheet music reading often leads to superior long-term retention and the ability to independently learn a wider repertoire. Furthermore, the long-held belief that adults are poor at acquiring music reading skills is being overturned. While children may have neuroplasticity on their side, adults possess highly developed pattern-recognition and analytical abilities that can make the learning process more efficient, provided the psychological barrier is overcome. The most effective approach for the dedicated student in 2025 is not to choose one exclusively, but to understand that these methods are complementary, not contradictory.

Deconstructing the Musical Alphabet

The Staff Demystified

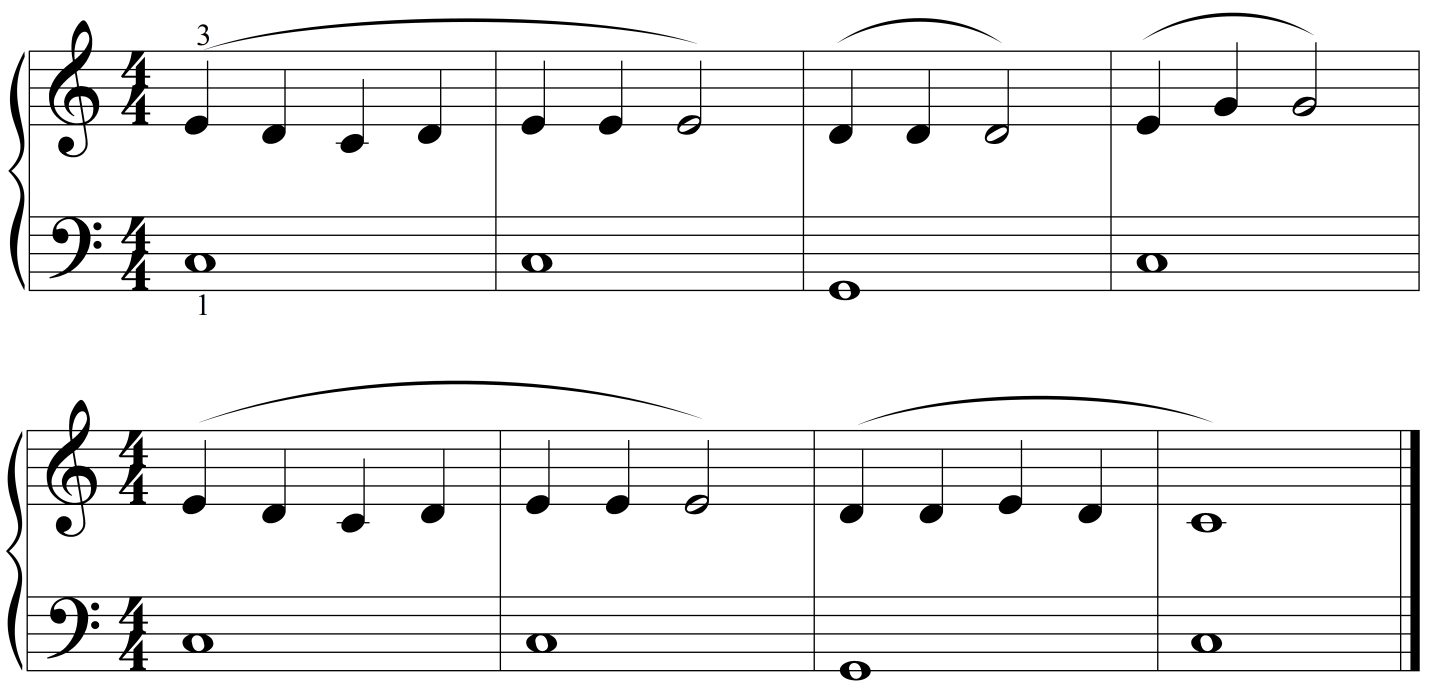

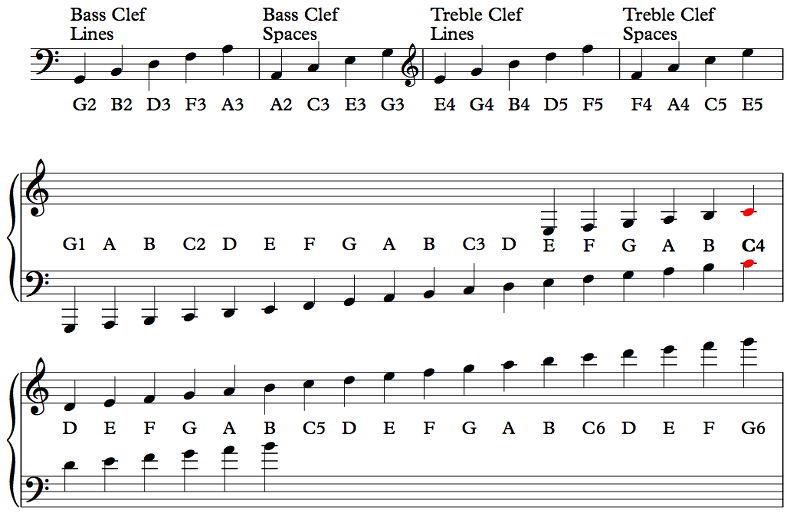

Treble Clef: Your Right Hand’s Roadmap

The treble clef, also known as the G clef, is the domain of your right hand, typically playing higher-pitched notes and the melody. The classic mnemonic for the lines, from bottom to top, is “Every Good Boy Deserves Fudge.” For the spaces, it’s even simpler: they spell F-A-C-E. However, if these don’t resonate, try a spatial approach: see the bottom line, E, as the note just below middle C, and the top line, F, as the note that feels high on the keyboard. A common beginner mistake is trying to remember each note in isolation. Instead, learn a few “anchor” notes. For instance, the note in the first space is F, and the note on the first line is E. Once you know these, you can count up or down to find any other note, solidifying the spatial relationship between the staff and the piano keys.

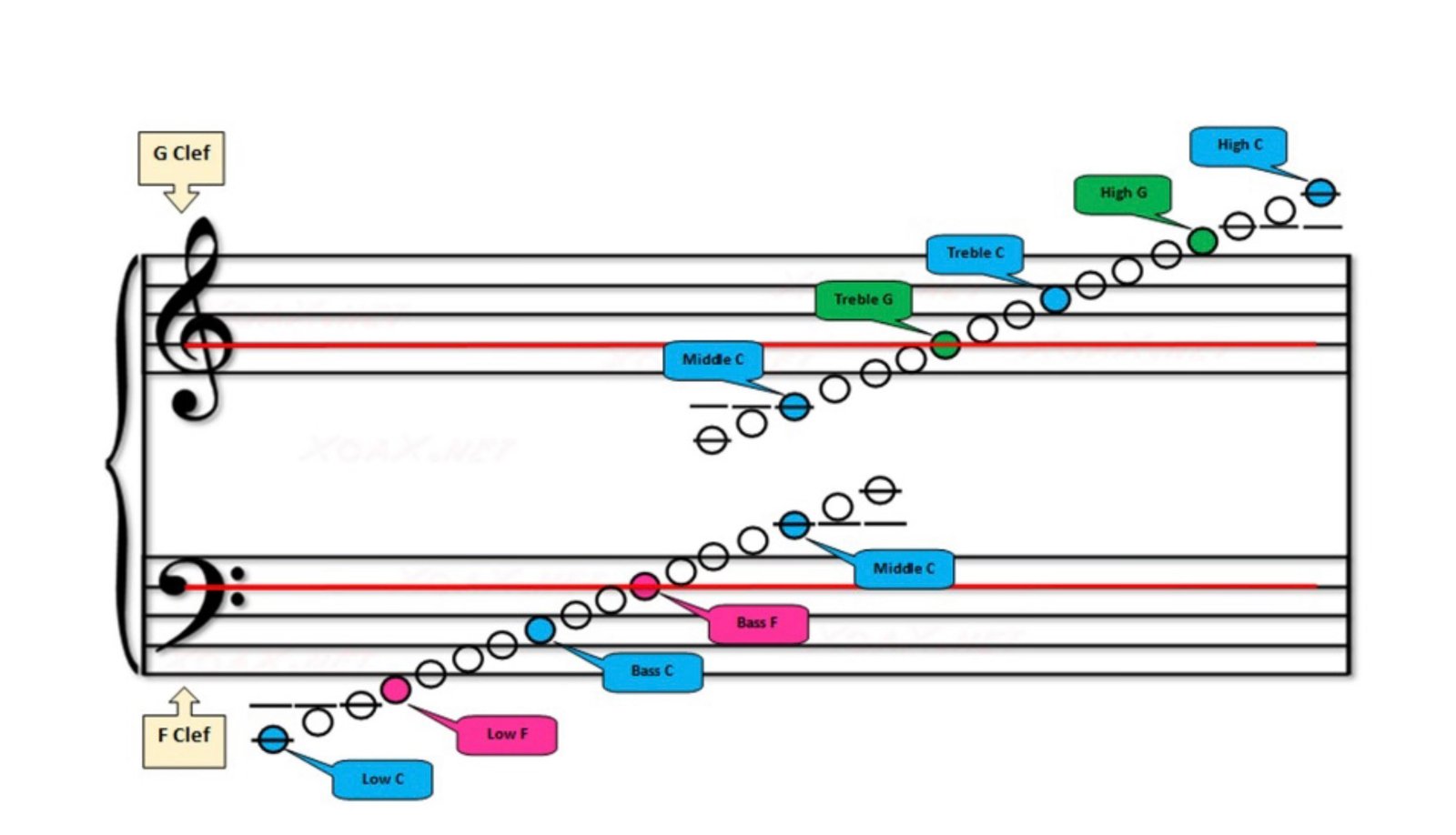

Bass Clef: Left Hand Navigation

The bass clef, or F clef, is your left hand’s territory, handling the lower-pitched notes and harmony. The mnemonic for its lines, from bottom to top, is “Good Boys Do Fine Always.” For the spaces, “All Cows Eat Grass” works perfectly. The true key to unlocking the bass clef is understanding its connection to the treble clef through Middle C. Middle C is written on its own tiny ledger line, positioned exactly between the two staves. On the piano, it is the C closest to the center. From this pivotal point, you can navigate downward into the bass clef and upward into the treble clef. Integrating both clefs is the foundation of hand coordination; your brain learns to process two streams of information simultaneously, which is the ultimate goal of piano literacy.

Note Values: The Rhythm Code

Duration Decoding System

Rhythm is the mathematics of music, but it doesn’t have to be complicated. Think of a whole note as a full pie. A half note is half of that pie, and a quarter note is a quarter of it. In 4/4 time, the most common time signature, a whole note gets 4 beats, a half note gets 2, and a quarter note gets 1. For faster notes, eighth notes get half a beat each and are often connected by a beam, while sixteenth notes get a quarter of a beat. The most practical counting method is to use a system of numbers and “ands” (for eighth notes) or “e-and-a” (for sixteenth notes). For example, two eighth notes would be counted as “1-and,” and four sixteenth notes as “1-e-and-a.” Clapping these rhythms before playing them builds an instinctual, physical understanding of timing that transcends abstract theory.

Rest Symbols: The Power of Silence

For every note value, there is a corresponding rest symbol that indicates a moment of silence of the same duration. A whole rest hangs from a line, while a half rest sits on a line. Quarter rests have a distinctive, squiggly appearance, and eighth and sixteenth rests have flags, similar to their note counterparts. The most critical skill for a beginner is to count these silences as actively as they count the sounds. A common rhythmic pattern in beginner music is a quarter note, followed by a quarter rest, and then two eighth notes (| ta [rest] ti-ti |). Mastering these combinations of sound and silence is what transforms a series of notes into music with pulse and phrasing.

The Pattern Recognition Breakthrough

Visual Chunking Strategies

Landmark Note System

The next leap in reading fluency comes from moving beyond individual notes to recognizing patterns. The most powerful starting point is the 3-key landmark method. Instead of memorizing every line and space, anchor your vision to three critical notes: Middle C, Treble G (the line the treble clef circles), and Bass F (the line between the two dots of the bass clef). These three notes form a stable triangle of reference points from which you can navigate the entire staff.

From these landmarks, you begin to read intervals—the distances between notes. Seeing that a note is a third above your landmark C is faster than calculating that it’s an E. Your peripheral vision learns to absorb clusters of notes as a single unit, much like you read a word instead of spelling out each letter. A 2025 study of adult learners found that those who practiced interval recognition for just five minutes daily doubled their sight-reading speed within a month.

Musical Shape Identification

Sheet music is filled with visual signatures. A scale passage, for instance, is a consecutive series of notes on lines and spaces. It creates a diagonal “staircase” shape on the staff. A chord appears as a stack of notes, and your hand can learn the shape for a C major triad (C-E-G) just as easily as your eye recognizes it. Arpeggios, which are broken chords, form a distinctive “zig-zag” pattern.

Composers also rely on repetition. When you spot a motif—a short musical idea—that repeats, either exactly or transposed, you no longer need to read it twice. You simply recognize it and execute it. This is the moment sheet music stops being a foreign code and starts to look like a familiar map.

Cognitive Shortcuts That Actually Work

Intervalic Reading vs. Note-by-Note

The single greatest shift for a budding pianist is the transition from note-by-note decoding to intervalic reading. Note-by-note reading is like sounding out “C-A-T” every time you see the word “cat.” Intervalic reading is seeing “cat” and instantly understanding its meaning. You train your brain to see the relationship between one note and the next. Is the next note a step up? A skip down? A leap of an octave?

This is the “word recognition” approach to music. You stop thinking “G, then B, then D,” and start seeing a “G major chord.” The impact on speed is profound. A beginner might take 30 seconds to laboriously decode a single measure. With intervalic reading, that same measure can be processed and played in under 3 seconds, because you’re recognizing a pattern you’ve seen a hundred times before.

Phrase Grouping Techniques

Music is a language, and like any language, it is organized into phrases—musical sentences. A phrase is a complete musical thought, often four or eight measures long, that typically ends with a cadence, music’s equivalent of punctuation. By identifying these phrases, you chunk the music into logical, manageable sections.

Look for breath marks (apostrophes in the music) and natural breaking points, often where a slur ends or a longer note value occurs. This allows for anticipatory reading: your eyes are always scanning one or two measures ahead of what your hands are playing. You are no longer reacting to each note as you play it; you are preparing for the next musical idea, ensuring a smooth and confident performance.

Practice Systems That Deliver Results

The 15-Minute Daily Framework

The most effective practice isn’t measured in hours, but in consistency and structure. A focused 15-minute daily routine, built on the pattern recognition skills we’ve just explored, yields faster progress than sporadic, unfocused sessions. This framework is designed to systematically wire your brain for musical fluency.

Structured Practice Sessions

The power of this system lies in its segmentation. Each five-minute block targets a fundamental skill, preventing cognitive overload while building compound fluency.

| Time Block | Focus Area | Sample Activities |

|---|---|---|

| Minutes 1-5 | Note Identification Drills | Flashcard practice targeting landmark notes and intervals; rapid identification of random notes on both clefs |

| Minutes 6-10 | Rhythm Clapping & Counting | Clapping and counting rhythms from new music, using a metronome; focusing on subdivisions (e.g., “1-and-2-and”) |

| Minutes 11-15 | Hands-Separate then Hands-Together | Applying the first two blocks to a real piece; mastering each hand’s part separately before a slow, combined attempt |

This structure ensures you are not just playing, but actively building the neural pathways required for reading. The 2025 consensus among piano pedagogues is that this type of distributed, varied practice is the most efficient path to proficiency.

Progressive Difficulty Scaling

To maintain momentum and avoid plateaus, your practice material must evolve in a predictable, manageable way. This is not about talent; it’s about a systematic approach.

- Weeks 1-2: Begin with single-line melodies centered in the C position (where your five fingers naturally rest on C-D-E-F-G). This reinforces landmark notes and step-wise intervals without the complexity of hand coordination.

- Weeks 3-4: Introduce simple hands-together arrangements. Start with pieces where both hands play the same rhythm, often with the left hand providing whole-note or half-note harmony, allowing you to focus on coordinating vertical alignment.

- Weeks 5-6: Incorporate basic chords (I, IV, V) and syncopated rhythms. You’ll begin to see the “stacked” shape of chords in the left hand and connect them to the melodic shapes in the right, directly applying the pattern recognition from before.

Sight-Reading Acceleration

Sight-reading is the ultimate test of your pattern recognition and practice systems. It’s a separate skill from practiced performance, and it requires its own training methodology.

The Non-Stop Method

The cardinal rule of sight-reading is to keep going. The goal is not perfection, but continuity and comprehension.

- Maintaining Tempo Despite Errors: Set a metronome to a painfully slow tempo. Your objective is to make it to the end of the piece without stopping, even if it means simplifying chords or dropping notes. This trains your brain to prioritize rhythm and flow over absolute accuracy, which is the hallmark of a good reader.

- Eye Movement Training: A common mistake is to look down at your hands. You must train your eyes to stay glued to the sheet music, trusting your fingers to find their place by touch and muscle memory. Your eyes should always be scanning ahead of the notes you are currently playing, absorbing the next musical phrase.

- Weekly Sight-Reading Challenges: Once a week, dedicate a session to reading entirely new, never-before-seen music. Track the number of measures you can play correctly at first sight. Over weeks, you will see this number climb, providing concrete evidence of your improving fluency.

Repertoire Building Strategy

Your sight-reading practice and your repertoire building are two sides of the same coin. One feeds the other.

- Starting with 5-Finger Pattern Pieces: Build initial confidence with a collection of short pieces that stay within a five-finger position. This allows you to focus on reading the note sequences and rhythms without the complication of moving your hand.

- Gradual Introduction of Position Changes: Once comfortable, select pieces that require a single, simple hand shift. You’ll learn to spot the visual cues—like a finger number or a large interval leap—that signal an upcoming move.

- Building a “Reading Portfolio”: Keep a log of all the pieces you have successfully learned to play. This portfolio is not just a record of achievement; it’s a library of patterns your brain has internalized. The more patterns you collect, the faster you will decode new music, because so much of it will already look familiar.

Technology Meets Tradition

The structured practice systems we’ve established are the engine of progress, but the modern pianist has access to a suite of digital tools that can act as a powerful turbocharger. The key is not to replace traditional methods, but to integrate technology in a way that amplifies and accelerates the learning process.

Digital Tools That Enhance Learning

In 2025, the most effective learners are those who blend disciplined, old-school practice with smart, targeted technological assistance. These tools provide the immediate feedback and engaging repetition that wires the brain for faster pattern recognition.

App-Based Reinforcement

The 15-minute daily framework can be supercharged with applications designed to turn fundamental drills into engaging, progressive games. This is distributed practice disguised as play.

- Note Identification Games with Instant Feedback: Apps like NoteQuest and StaffWars turn the tedious process of memorizing the grand staff into a fast-paced game. They adapt to your skill level, relentlessly targeting your weak spots—be it ledger lines or the alto clef—until every note becomes an instant, subconscious recognition.

- Rhythm Training Applications: Tools such as Rhythm Cat or Complete Rhythm Trainer allow you to clap or tap complex rhythmic patterns and receive instant, objective feedback on your accuracy. This builds a rock-solid internal metronome, which is the foundation for the “non-stop” sight-reading method.

- Progressive Sight-Reading Software: Platforms like Sight Reading Factory generate an endless supply of new, short musical excerpts tailored to your exact level. This eliminates the hunt for new material and provides the consistent, daily sight-reading challenge essential for building fluency, directly supporting the weekly challenges from your practice system.

Hybrid Learning Approaches

The future of music education isn’t a choice between a book and a screen; it’s the intelligent fusion of both.

- Combining Sheet Music with Video Tutorials: Learning a new piece by starting with the sheet music and then using a video tutorial to check for interpretation, fingering, and phrasing is a powerful hybrid method. It teaches you to decode the symbols on the page first, then uses the video as a verification tool, reinforcing the connection between symbol and sound.

- Using Light-Up Keyboards for Visual Reinforcement: For absolute beginners, keyboards with LED-guided keys can bridge the gap between finding a note on the staff and locating it on the keyboard. This tool is most effective when used sparingly to overcome initial hurdles, as the long-term goal is to develop a mental map of the keyboard independent of visual aids.

- Recording and Analysis for Self-Assessment: The smartphone in your pocket is one of the most powerful practice tools available. Regularly recording your playing—especially your sight-reading sessions—and listening back critically allows you to become your own teacher. You will hear rhythmic inaccuracies and hesitations that you didn’t notice while you were playing, providing invaluable feedback for your next session.

The Paper vs. Screen Debate

As you build your repertoire and practice habits, you will inevitably face the choice between traditional printed music and digital scores on a tablet. Each has its place in a modern pianist’s toolkit.

Traditional Sheet Music Benefits

There is a tangible, historical connection to paper that technology has yet to replicate fully. Its advantages are rooted in physicality and tradition.

- Annotation Capabilities and Personal Marking Systems: The physical act of writing on a score—circling dynamics, penciling in fingerings, highlighting key changes—creates a deeper cognitive connection to the music. Your annotated score becomes a personalized map of your interpretive decisions and technical solutions.

- Physical Connection to Musical History: Handling a printed score, especially from a critical edition, connects you to a centuries-old tradition of musicianship. There is an irreplaceable feeling of handling the same “blueprint” that musicians have used for generations.

- Performance Preparation Standards: The concert world still runs on paper. Practicing with physical scores prepares you for the reality of recitals and exams, where page turns are a physical skill and there is no risk of a dead battery or a glitching screen.

Digital Advantages

For the practicing musician, the convenience and features of digital sheet music are transformative, particularly in the early and intermediate stages of learning.

- Scroll-Free Page Turns: With a tablet and a Bluetooth page-turn pedal, you can play through lengthy pieces without the dreaded page-turn scramble. This supports the core sight-reading principle of maintaining a continuous flow, no matter the complexity of the piece.

- Built-in Metronome and Recording Features: Your digital sheet music app can be seamlessly integrated with a metronome click-track, and your recording setup is always at hand. This creates an all-in-one practice environment that directly facilitates the structured, focused sessions we’ve outlined.

- Access to Vast Libraries of Music: Instant access to platforms like IMSLP or subscription services means you never run out of sight-reading material. This democratizes music learning, giving you the freedom to explore and build your “reading portfolio” with an almost infinite library of music from every genre and era.

Overcoming Psychological Barriers

The most sophisticated practice system and the most powerful digital tools can be rendered useless by a single, formidable adversary: our own mind. For the adult beginner, the journey of learning to read sheet music is as much about managing psychology as it is about mastering notation. The belief that musical talent is a fixed, inborn gift is one of the greatest impediments to progress. The reality, as modern learning science confirms, is that fluency is a skill built through structured practice.

The Adult Beginner’s Mindset

Adults bring a lifetime of experiences to the piano bench, which is both a blessing and a curse. The self-awareness that allows for disciplined practice can also manifest as a paralyzing fear of sounding foolish. The key to unlocking potential lies not in wishing for more “talent,” but in actively cultivating the right mindset.

Redefining “Musical Talent”

The concept of “musical talent” is often a mirage. What we perceive as talent in others is almost always the visible result of hours of dedicated, deliberate practice. Applying a growth mindset to music reading means understanding that your ability is not fixed; it is a muscle that strengthens with every session.

- Growth Mindset Application to Music Reading: When you struggle to read a bass clef note instantly, the growth mindset reframes this not as a failure, but as a signal. It indicates a specific neural pathway that hasn’t yet been fully insulated with myelin. The “struggle” is the precise process of building that pathway. Each time you correctly identify a note after a moment’s hesitation, you are wrapping that connection in another layer, making it faster and more reliable for next time.

- Celebrating Small Victories in the Learning Journey: The path to fluency is paved with micro-achievements. Did you successfully play a measure without stopping? That’s a victory. Did you correctly identify an F# in the key signature? Another victory. By focusing on these small, daily wins, you build a positive feedback loop that makes the process enjoyable and sustainable, rather than fixating on the distant goal of playing a Chopin Nocturne.

- Comparative Analysis of Child vs. Adult Learning Advantages: While children may have neuroplasticity on their side, adults possess powerful learning tools that are often overlooked. Adults have superior focus, better problem-solving skills, and a clearer understanding of why they want to learn. An adult can grasp music theory concepts like key signatures and chord structure in a way a child cannot, using logic to shortcut the learning process. Your ability to understand the “why” behind the “what” is a significant advantage.

Anxiety Reduction Techniques

Performance anxiety, even in the private context of your own practice room, can trigger a fight-or-flight response that shuts down the precise, analytical parts of the brain needed for reading music. The solution is to systematically desensitize yourself to the pressure.

- Performance Preparation Methods: Simulate low-stakes performances regularly. This could mean recording yourself once a week, or playing a single, prepared piece for a family member. The goal is to acclimatize your brain to the adrenaline rush of being “on display,” teaching it that this state is not a threat but a normal part of making music.

- Error Recovery Strategies During Practice: The single most important skill for a sight-reader is the ability to keep going. Practice this intentionally. When you make a mistake in a practice session, do not stop and correct it immediately. Instead, force yourself to continue to the end of the phrase or section. This trains the crucial habit of error recovery, separating the act of reading from the act of perfection.

- Building Confidence Through Prepared Pieces: While most of your practice should be focused on new material, always keep one or two “party pieces” in your back pocket—simple pieces you have mastered to a high level. Returning to these pieces when you feel discouraged provides a powerful reminder of your capabilities and restores confidence.

The Motivation Equation

Motivation is not a mysterious force that you either have or you don’t; it’s a resource that can be engineered. The equation for sustained motivation is simple: consistent progress plus a sense of community equals long-term commitment.

Setting Achievable Milestones

A goal like “becoming a good sight-reader” is too vague and distant to be motivating. You need a series of stepping stones that provide a constant sense of forward momentum.

- First 10-Note Recognition Goal: Before you even worry about rhythm, set a goal of being able to instantly name 10 notes—five in the treble clef and five in the bass clef. Achieving this small, concrete goal within your first few days builds initial confidence.

- First Complete Piece Mastered: Your first piece doesn’t have to be “Für Elise.” It can be a four-measure beginner’s étude. The act of taking a piece of sheet music from start to finish, decoding every symbol and producing a coherent musical phrase, is a profound milestone that proves the system works.

- First Sight-Reading Accomplishment: Set a goal to sight-read one new, short piece of music every day for two weeks. At the end of the period, return to the very first piece you read. The dramatic improvement in your fluency and ease will be one of the most powerful motivators you can experience, providing tangible proof of your brain’s ability to adapt and learn.

From Reading to Musical Fluency

The moment you stop seeing a page of sheet music as a rigid set of instructions and start viewing it as a conversation with the composer is the moment you cross the threshold from literacy to fluency. This transition is not about playing more notes faster; it’s about understanding that the printed page is merely the skeleton of the music. The artist’s job is to breathe life into it. In 2025, the most successful piano students are those who master this art of musical interpretation alongside their technical skills.

The Transition to Expression

True musicality begins where the basic notes end. The symbols beyond the staff—the ps, fs, slurs, and accents—are the composer’s vocabulary for emotion and narrative. Learning to read these markings with the same fluency as the notes themselves is what separates a mechanical performance from a moving one.

Moving Beyond the Notes

Consider two pianists playing the same piece note-perfectly. One leaves the audience cold; the other brings them to tears. The difference lies entirely in their interpretation of the expressive markings.

- Dynamic Marking Interpretation: The markings

pp(pianissimo) andff(fortissimo) are not binary switches but points on a vast spectrum of volume. The real magic lies in the transitions between them—the crescendo (<) that builds tension and the decrescendo (>) that releases it. A skilled reader doesn’t just play louder or softer; they shape musical phrases by treating dynamics as a continuous, fluid landscape. - Articulation and Phrasing Development: Articulation marks are the grammar of music. A staccato dot tells you to detach a note; a slur indicates a legato, connected phrase. But phrasing is the higher-level skill of grouping notes into musical sentences, much like a compelling speaker groups words. It involves a subtle “breath” or a slight relaxation before a new phrase begins, giving the music structure and meaning.

- Personal Interpretation Within the Composer’s Framework: The composer’s framework is a playground, not a prison. A ritardando (slowing down) at the end of a section has no fixed speed; it is a matter of taste and feeling. Your personal interpretation is the color you bring to the black-and-white outline of the score. It is how you decide to voice a chord to bring out a hidden melody or how you use rubato (stolen time) to add emotional weight, all while respecting the composer’s fundamental intentions.

Improvisation Within Structure

Many classically trained musicians freeze at the idea of improvisation, believing it requires a magical, innate talent. In reality, it is a skill that can be systematically developed, starting from the safety of the written page.

- Adding Simple Embellishments to Written Music: Begin by adding a single, tasteful trill to a long note in a piece you know well. Or, turn a straight quarter note into two eighth notes. These small, controlled deviations from the score are the first steps toward making the music your own. They teach you that the score is a guide, not a dictator.

- Chord-Based Variations on Melodic Themes: Once you can identify the underlying chord progression of a piece (e.g., C Major, G7, C Major), you can experiment. The next time you play the melody, try using the notes of the accompanying chord to create a simple counter-melody or a new rhythmic pattern for the left hand. This connects your reading skills directly to your creative brain.

- Creating Personal Cadences and Endings: A cadence is a musical punctuation mark. Take a simple piece and, instead of playing the final chord as written, try creating your own ending. You could end on a different chord for a surprise, or slow down and arpeggiate the final chord for a more dramatic conclusion. This is a powerful exercise in understanding musical syntax and developing creative confidence.

Continuous Improvement Pathways

The “what next?” question can be paralyzing after you’ve mastered the basics. The answer lies in a structured, self-renewing system for growth.

- Progressive Repertoire Selection Strategy: Your choice of music is your primary curriculum. Adopt a “plus-one” principle: always have one piece in your practice rotation that is slightly above your current comfort level. This ensures you are constantly acquiring new skills and tackling new technical and interpretive challenges.

- Technical Exercise Integration: Scales and arpeggios are often seen as drudgery, but they are the calisthenics that build a fluent musician. The key is to practice them with a purpose. Don’t just play a C Major scale; play it with a crescendo, or staccato, or in a specific rhythmic pattern. This transforms mechanical exercise into meaningful practice for both fingers and mind.

- Regular Assessment and Goal Adjustment: Set aside time every three months for a personal “audit.” Record yourself playing pieces from three months prior and compare them to your current work. What has improved? Where are the persistent weaknesses? Use this objective data to set specific, measurable goals for the next quarter, ensuring your practice remains focused and effective.

The Sight-Reading Virtuoso Track

For some, the ultimate goal is not just to play, but to be able to open any piece of music and bring it to life on the spot. This is the skill of the accompanist, the conductor, and the truly versatile musician.

- Daily Sight-Reading Habit Formation: Fluency in any language requires daily reading. Dedicate the first 5-10 minutes of every practice session to reading something you have never seen before. The material should be easy enough that you can maintain a slow but steady pulse without stopping. This daily exposure builds pattern recognition at an unconscious level.

- Genre Diversification for Reading Flexibility: Don’t just read classical music. In 2025, resources are abundant. Spend one week reading jazz charts, the next week reading pop lead sheets, and the following week reading a Baroque dance. Each genre has its own notational conventions and rhythmic idioms. By diversifying your reading diet, you become a more agile and adaptable musician.

- Performance Under Pressure Training: The final step is to simulate real-world conditions. Set a timer for one minute to scan a new piece, then hit record and play it through without stopping, mistakes and all. This practice trains your brain to process information quickly and recover from errors gracefully—the hallmark of a confident sight-reader. For those seeking a comprehensive system that guides you from decoding your first note to achieving this level of expressive, lifelong fluency, the right program makes all the difference.

Your Personal Practice Revolution

The journey from decoding notes to making music requires more than just willpower; it requires a system. The most successful pianists in 2025 aren’t necessarily the most talented—they are the most strategic. They understand that a personalized, structured plan is the engine that transforms scattered efforts into measurable progress. This is about engineering your own musical breakthrough.

Customized Learning Plan Development

A generic plan yields generic results. The key to rapid advancement is a learning path tailored to your unique starting point, aspirations, and daily life.

Assessment and Goal Setting

Before you can map your route, you must pinpoint your exact location. Honest self-assessment is the cornerstone of effective practice.

- Current skill level evaluation parameters: Ask yourself specific questions. Can you identify any note on the treble and bass clef within two seconds? Can you consistently maintain a steady rhythm while playing a scale? Can you play hands together comfortably at 60 beats per minute? Rate your skills on a scale of 1-5 in areas like note reading, rhythm, hand coordination, and dynamic control. This creates a baseline data set, not a vague feeling of your ability.

- 3-month, 6-month, and 1-year realistic targets: Transform vague desires into concrete objectives. A 3-month target might be, “Sight-read a Level 1 piece from the Faber Adult Piano Adventures book with fewer than 3 pauses.” A 6-month goal could be, “Perform Beethoven’s ‘Ode to Joy’ with expressive dynamics for family.” A 1-year vision might be, “Play the lead sheet of a pop song with both melody and a simple chord accompaniment.” These targets become your roadmap.

- Practice schedule optimization based on lifestyle: The “ideal” 2-hour practice session is a myth for most. It’s far more effective to have a consistent 25-minute daily session than a sporadic 3-hour marathon. Analyze your weekly schedule. Can you dedicate 20 minutes every morning before work? Can you do two 15-minute sessions? The goal is consistency and frequency, not just total hours.

Resource Compilation Strategy

In an age of infinite digital resources, curation is a superpower. Your toolkit should be lean, effective, and tailored to your plan.

- Building a personal sheet music library: Start with a structured method book (like Alfred’s or Faber) as your spine. Then, supplement it with a growing collection of repertoire. Use a simple system:

Genre Beginner Intermediate Classical Bach’s Minuet in G Clementi’s Sonatinas Pop Simple lead sheets Arrangements with chord inversions Jazz 12-bar blues scales Basic standard melodies - Tool and application selection criteria: Use technology to accelerate learning, not to create distraction. A good metronome app is non-negotiable. A flashcard app for note drilling can build speed. Sheet music apps like forScore are excellent for organization. The criteria for any tool should be: Does it solve a specific problem in my practice? Does it save me time? Does it make practice more engaging?

- Teacher vs. self-study decision factors: This is not a binary choice but a spectrum. A good teacher provides immediate feedback, corrects technique, and offers curated repertoire—this is invaluable for beginners. Self-study requires immense discipline but offers flexibility. Consider a hybrid model: monthly check-ins with a teacher to correct course, supplemented by disciplined self-study in between. For those pursuing self-study, a comprehensive, structured course is essential.

The 90-Day Transformation Timeline

A long journey is best broken down into a series of short sprints. This 90-day framework provides the momentum and focus needed to build lasting skills.

Phase 1: Foundation Building (Days 1-30)

This phase is about creating an unshakable foundation. The goal is not speed, but accuracy and automation.

- Note recognition automation: Spend five minutes daily with flash cards or an app until you can identify any note, in both clefs, without hesitation. This is the phonics of music.

- Basic rhythm mastery: Clap and count rhythms daily. Start with whole, half, and quarter notes. Use a metronome to internalize a steady pulse. The body must feel the rhythm before the fingers can play it.

- Simple piece completion: Your goal is to fully learn 2-3 very simple pieces in this period. Pieces like “Ode to Joy” or simple folk songs are perfect. Completion builds confidence and reinforces the connection between reading and playing.

Phase 2: Skill Integration (Days 31-60)

With the fundamentals on autopilot, you now focus on the core technical challenge of the piano: coordination.

- Hands coordination development: Practice hands separately first, then together, excruciatingly slowly. Use a “chaining” method: master one measure hands together, then the next, then connect them. The brain needs time to build the new neural pathways for independent hand motion.

- Position change fluency: Begin learning pieces that require your hand to move from one position to another. Practice the motion of the shift itself—lifting, moving, and landing gracefully—separate from the notes.

- Intermediate piece capability: Tackle a piece that incorporates both hands together, simple position shifts, and a wider range of notes. A piece like Bach’s “Minuet in G” or a simplified version of “Gymnopédie No. 1” represents a significant milestone in reading and execution.

Phase 3: Fluency Development (Days 61-90)

The final phase is where the skills coalesce into genuine musicianship. You shift from learning music to making music.

- Sight-reading simple pieces: Dedicate the first 10 minutes of practice to playing entirely new, simple material from a beginner’s book. The rule is: keep going, no matter what. This trains your brain to process information in real-time.

- Expressive playing incorporation: Now, as you learn a new piece, your first question is not “What are the notes?” but “What is the story?” Go back to your Phase 2 pieces and relearn them, this time focusing intensely on the dynamics (

p,f, crescendo), articulation (staccato, legato), and phrasing. - Personal repertoire establishment: By day 90, you should have a collection of 5-7 pieces that you can play comfortably and expressively from memory. This is your “party piece” repertoire—music you own and can share with pride, proving your transformation from a note-reader to a musician. For a guided journey that maps this entire 90-day revolution out for you, turning theory into daily, achievable practice, a structured system is invaluable.

Your Path to Musical Fluency Begins Now

The journey from decoding individual notes to achieving genuine sheet music literacy is built on three foundational pillars: systematic pattern recognition through landmark notes and intervalic reading, consistent structured practice that builds neural pathways, and the right mindset that embraces mistakes as part of learning. The research is clear—while methods like mimicry offer faster initial rewards, the deep structural understanding fostered by traditional sheet music reading leads to superior long-term retention and the ability to independently learn complex repertoire. Your age isn’t a barrier but an advantage, as adults bring highly developed analytical abilities to the learning process.

No comment